By Jane Dummer, RD

Wheat farming in Canada

Wheat is grown coast to coast in Canada on all sizes of family farms. Canadian wheat farming dates back to 1842 when Scottish immigrant Robert Fife cultivated wheat seeds from Scotland on his farm in Peterborough, Ontario. Fast forward to today: Canada is the sixth largest wheat producer in the world. Canadian wheat is known for its quality, versatility and protein content.

Canadian farmers like growing wheat because of its agronomic appeal as an excellent crop rotation to build and support healthy soil and the high demand for Canadian wheat both domestically and globally.

What type of wheat is grown in Canada?

There are ten wheat classes grown in Western Canada and seven in Eastern Canada. Farmers choose the wheat class and variety of wheat that grows best on their farms. The most common classes of wheat include:

- Canada Western Red Spring (CWRS)

- Grown primarily in Western Canada producing a high protein content excellent for milling, bread and noodle quality.

- Canada Western Amber Durum (CWAD)

- Canada is the world’s leading exporter of CWAD wheat, and it’s mainly grown in southern Alberta and Saskatchewan. It’s renowned for its high protein content, yellow colour and high semolina yield used in superior quality pasta and couscous.

- Canada Eastern Soft Red Winter (CESRW)

Wheat on the farm – Seeding

Seeding is one of the most important and crucial tasks for the farmer. Timing, depth and rate rely on specialized technology, so planning is key in this step. Western Canada farmers typically plant spring wheat seeds in May, however if the snow melts early, seeding can occur in April. It requires approximately four months to mature depending on the weather conditions.

Most winter wheat is farmed in Ontario. These Eastern farmers plant winter wheat seeds in the late summer or early fall. The winter wheat seeds lay dormant during winter. It takes about 10 months to be ready for harvest, usually in July.

Wheat on the farm – Growing

A recent study suggests that Canadian producers, particularly in Saskatchewan and Western Canada, are producing some of the least carbon-intensive crops in the world. This is driven by the widespread adoption of various innovations and sustainable farming practices, including minimal- to no-till farming and a robust crop rotation system. In addition, variable-rate application of fertilizer and reliance on rain fall and snow for soil moisture (very few Canadian wheat acres have irrigation systems) are factors enhancing the sustainable growing conditions for wheat.

As the wheat plants grow, they flower. The flowers pollinate to form the seeds. As the wheat plant matures in the field, the seeds increase in size, accumulating the nutrients that are important to human nutrition. These seeds, also called kernels, are the part of the wheat plant used to make a wide range of foods.

Canadian farmers rely on rotation of crops. Wheat is an important crop for breaking disease cycles in other crops and building soil health. For example, spring wheat stubble, meaning the straw left behind after harvesting in late summer and early fall, captures snow during the winter. This is also vital for carbon capture in the soil to produce an ideal environment for the next planting.

Wheat on the farm – Harvesting

Wheat that is planted in the springtime is harvested in late August and September. Some varieties of wheat can be planted in the fall that remain in a vegetative state over the winter. Winter wheat harvesting occurs mostly in July. The kernels need to be dry and firm to harvest. Massive machines called combines cut the straw, pull the heads of the wheat plant into the machine, then thresh and separate the straw from the grains. The straw is blown out of the back of the combine, spread across the field a lot like compost, and the grain is moved into the grain tank until unloading. A mature wheat field can be harvested at a steady pace throughout the day and even into the evening, depending on conditions.

Wheat on the move – Transportation and Storage

After harvest, farmers transport wheat kernels from their on-farm grain storage to handling facilities called grain elevators where their wheat is blended with those of other farmers and stored. Grain elevators are found throughout Canada for domestic or global sales. Elevators segregate wheat of the same class and protein level before shipping onwards in the supply chain.

Wheat on the move – Milling

Milling is the term used to describe the process of grinding or crushing grain kernels into flour or semolina so they can be used to make food. Today, there are approximately 55 commercial wheat and oat mills operating from coast to coast. Most wheat arrives at the mill from grain elevators. Once all testing, safety and quality controls are complete, the kernels are ready to mill. Capacities of most flour mills vary from 50 to 2,000 tonnes of wheat per day. A flour mill may produce only one type, or as many as 50 types of flour.

Canadian mills use state-of-the-art milling equipment and technology. This involves rolling, grinding and sifting into the component parts of bran, germ and endosperm. Different wheat flours are made from a ratio of these parts and have different applications. The most common are whole grain whole-wheat, whole-wheat flour, and white enriched wheat flour, known as all-purpose flour. Wheat germ and bran are also sold in grocery stores.

Once milled, some flours are fortified and/or treated with additives or enzymes to enhance appearance and improve functionality. By legislation in Canada, refined wheat flour must be enriched with vitamins and minerals to replace the nutrients lost (or removed) during the milling process. Enrichment usually involves the addition of vitamins and minerals in powder form. Mandatory nutrients include thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, folic acid and iron.

Wheat on the fork

Canada grows about seven times more wheat than what we can consume domestically. About 20 million tonnes of Canadian wheat is exported to countries around the world each year. Our wheat is sought after for its protein, quality and versatility.

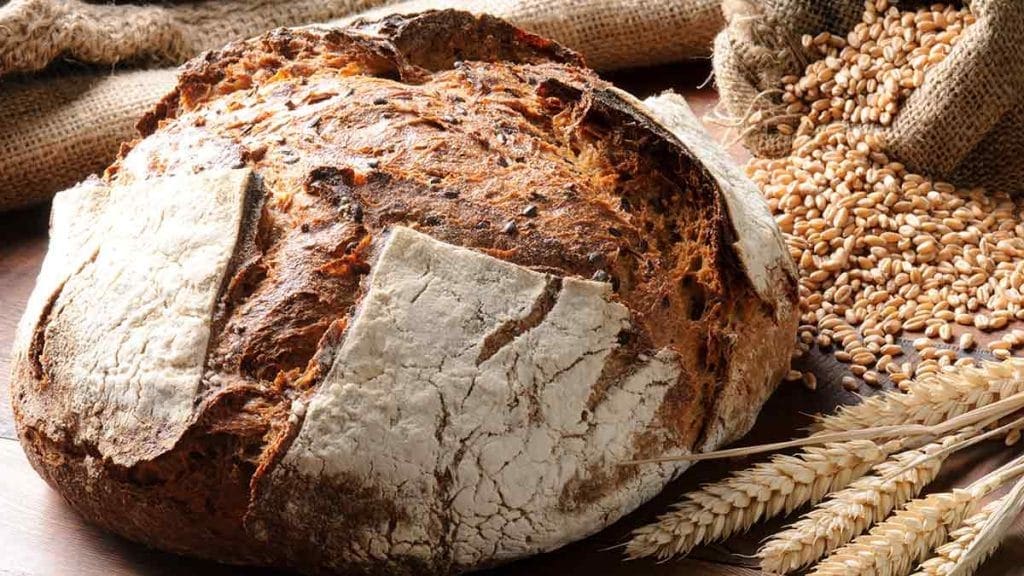

Approximately 10 per cent of all wheat milled in Canada finds its way directly to consumers for at-home baking and food preparation as all-purpose flour, cake and pastry flour, wheat bran and various bakery mixes. The other 90 per cent of wheat milled in Canada reaches consumers as freshly prepared and packaged foods. The largest portion of wheat eaten by consumers in Canada is in the form of breads, bakery products, breakfast cereals, crackers and biscuits, ready-to-cook dry pasta, and fresh and frozen pasta products.

Farm to fork journey of wheat

Next time you’re enjoying a baked good or pasta dish, remember the farm to fork journey of wheat in Canada. Every step of the process involves many people devoted to sustainable farming practices, quality and safety controls, along with flavour and texture innovations to bring you first-class foods made with Canadian wheat. Canada grows about seven times more wheat than what we can consume domestically. About 20 million tonnes of Canadian wheat is exported to countries around the world each year. Our wheat is sought after for its protein, quality and versatility.

Discover more about crops grown in Canada or explore tasty wheat-based recipes by checking out these articles!

- From Our Fields To Your Table: Growing Oats In Canada

- From Orchards To Store: The Apple Journey

- How Are Dry Peas Grown?

- How Are Sugar Beets Grown In Canada?

- How Did Canada Become A World Leader In Lentils?

- Canadian Ingredient Spotlight: Wheat

Creamy Mushroom Alfredo

Creamy Mushroom Alfredo