By Savannah Gleim

Before we dive too deep, let me first be upfront: I am not super literate when it comes to chemicals. I am just very curious, so when I do not know something, I look it up. The first reason is that we live in 2025, where we have a supercomputer in our pockets, there is no reason not to look it up. The other reason is that I am married to a very cool dude, a science teacher, and I want to be able to ask him questions and understand what he is talking about. My husband Warren is a high school science teacher with a degree in chemistry. Also, I do a lot of work in understanding science for my job at the University of Saskatchewan and our blog SAIFood, and I find it is important to understand the chemistry behind many of our foods and agricultural inputs, it leads to many discussions about chemical literacy.

Plus, I am a strong believer in science and our regulation policy here in Canada, so when it comes to talking about chemicals, whether it is for agriculture or the composition of our food, I am biased to trust the science and safety behind it.

The Chemistry of Life

It’s all chemical. All matter is composed of substances which are identified as chemicals. The matter all around us is composed of different chemical elements that are arranged in different combinations or ratios. In total, there are 118 chemical elements (only 92 naturally occurring, the rest man-made!), and when they combine through different chemical reactions, we get different products. H2O is water, and it is the composition of 2 hydrogen atoms with 1 atom of oxygen. Everything is composed of chemicals, but some are more complex than others and that can make them more difficult to understand. For example:

- Sucrose (sugar) is C12H22O11 which is a ratio of 6 carbon: 22 hydrogens: and 11 oxygen.

- Steel doesn’t have just one set chemical formula, but it is the combination of iron and carbon, along with other metals and sometimes alloys.

- Diamonds are pure carbon, formed by extreme heat and pressure.

- Living organisms are mostly made up of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen (CHON), which make up 95% of the mass of the organism. The human body is roughly 65% oxygen, 18.5% carbon, 9.5% hydrogen, 3.5% nitrogen, and 3.5% other chemical elements like calcium, phosphorus, and 15 others.

Chemical Literacy

So, what Is chemical literacy? I am not suggesting you need to remember back to your high school years and know about stoichiometry or thermodynamics calculations in our daily life – that’s not being chemically literate for the everyday user. It is really about knowing enough to make good decisions in your daily life, understanding marketing and propaganda tactics, and knowing when to be afraid and when not to be afraid. This is a higher-value skill for the average person.

In other words, chemical literacy is being able to understand and use chemistry in everyday life. It involves three main parts: knowing chemistry, being aware of its importance, and applying it effectively. When it comes to chemical literacy, there is well-documented research on the topic by Dr. Joseph Schwartz et al. in three of their publication in 2006a, b, and 2011. These authors review literacy and what it means at a high school level, which is where most of us get introduced to the topic, but also where many of us last learn about it. From their research, they divide chemical literacy into four segments:

- scientific and chemical content knowledge,

- chemistry in context,

- higher-order learning skills, and

- affective aspects.

However, that isn’t very clear, and not even my husband who is chemically literate understood what was meant by “affective aspects”. So maybe rather than focusing on what the ‘academic’ research world thinks of chemical literacy, let’s be more practical. When I refer to chemical literacy, I am more focused on being aware of its importance and having the content and context (1 and 2) to understand what I am being presented with. Everything is composed of chemicals, and therefore understanding them can’t hurt.

I hear all the time, even from my friends and family, about eating only “clean ingredients” or if you can’t read (or pronounce) it, you shouldn’t eat it. Oh, this one grinds my gears, first of all, because I am really poor at reading (I am a phonetic reader), but also because this is just silly! Food labels are not written with chemical elements listed, they are written according to their ingredient or chemical names, like sucrose, and not C12H22O11.

Going bananas for chemicals

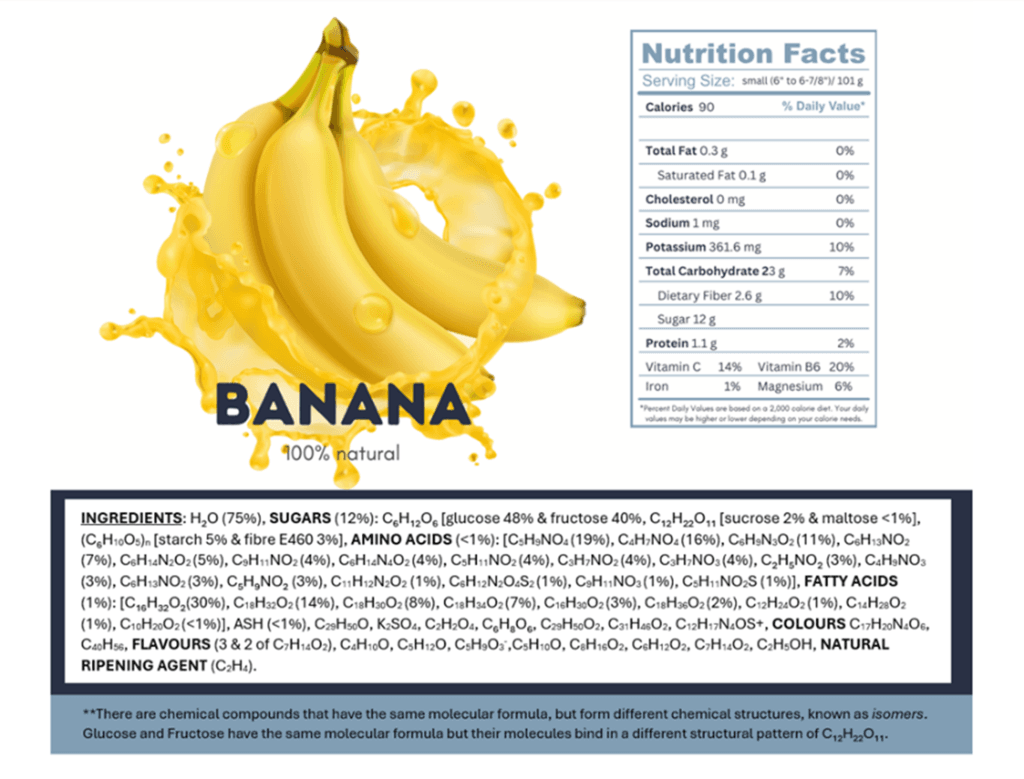

Let us take a simple example, the banana. Now if a banana were to have a food ingredient label, it would say 100% banana, and if it were an ingredient in another food, it would be listed simply as banana. Easy, right!? But what if you listed the composition of that banana, what would that label look like?

James Kennedy, a chemistry teacher and author has a great source of infographics on his website which breaks down the ingredients of a banana: not the chemical composition, but what would be the ingredient name. We know that bananas are safe to eat, but if you were to live by the mantra of if you can’t pronounce it you shouldn’t eat it, would you eat it? Can you pronounce phenylalanine or phylloquinone? Phenylalanine is an amino acid (C9H11NO2) that is used to make protein. Without it – no muscles, cartilage, bones, or cells. What about phylloquinone, whose chemical formulation is C31H46O2 and is described as 2-methyl-3-(3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadec-2-enyl)naphthalen1dione? Good luck saying that! It is vitamin K1, a fatty acid which is needed for “blood coagulation and bone metabolism”.

Of course, we know that bananas are safe to consume, but this just aids in the argument that we need to question the chemical information we are presented with and work to understand what is being presented to us. So, whether it’s a banana or a complex list of ingredients, they are both composed of multiple chemicals, but that doesn’t mean it is bad or good either.

Savannah Gleim, 2024

How do I become chemical literate?

We live in an age where there is so much information and too much access to misinformation, and therefore I don’t think it is your responsibility to become completely chemically literate. Do I think it would be beneficial? Sure, but I also know it would be beneficial if I learned to change my car’s oil or how to skate backward, but I am 36 years old and haven’t yet and I am getting by just fine. It is the steps within being chemically literate and informed that I think are important.

First off, knowing that everyone and everything is composed of chemicals is good to acknowledge, chemicals are the building blocks of all matter. It helps us remember that chemicals are not bad. As explained by my husband, “Few chemicals are inherently bad for you. Chemical safety is almost always about how much.” Many are bad for you if you get too much, and some (like vitamins for example) are bad for you if you get too little. Bottom line: next time you are curious or are presented with the idea that the chemicals in something are either good or bad for you, it’s important to ask why. What makes it good or bad, and taking the time to inquire about it–that is helping you to gain chemical literacy.

Find more articles about science, sustainability, and innovations in food and agriculture from Savannah and colleagues at the SAIFood Blog.

Grain Dryers: Advanced Equipment For Moisture & Quality Control

Grain Dryers: Advanced Equipment For Moisture & Quality Control